Follow the links to parts 2, 3, 4, and 5.

In recent weeks, I’ve felt an itch to go back to church. Not so much because I believe in anything the church teaches anymore — at least not on a literal level — and not out of any sense of obligation or guilt. I think it’s just that I’ve always felt a pull toward the spiritual life, and since church was one of the few things that brought me some peace and stability in my formative years, I’m sure I have a predisposition to find comfort and meaning there as an adult.

I’ve been in and out of church for most of my adult years. The familiar stories, the rituals, the traditional annual rhythms of the church calendar, the ethical teachings, the beautiful church architecture, the rich history, and the gorgeous singing all combined to put me in a warm, fuzzy place for a little while every week.

I’ve read stories of atheists who attend church because of the peace it brings them, and because they believe in the importance of ritual and tradition. There’s something to be said for that as our society becomes increasingly unmoored from anything that could prevent it from spinning off into chaos.

But while I’m not an atheist, I also don’t know if I could fake my way through a service every week, being surrounded as I would be by throngs of true believers who would want to have earnest religious conversations with me that I couldn’t relate to if I were being true to myself.

That’s what put me in the mind to lay out some thoughts here. Maybe some of them will resonate with you, but this is a thought experiment more than anything else.

First, a fun fact about me: I’m a mail-order minister. All that means in a practical sense is that I can legally marry people. But I’ve always had an interest in running my own little chapel, even if no one else ever attended. I have shelves and shelves of books dealing with religion and spirituality, both mainstream paths and obscure ones. I’ve been studying independently for years. I have a head full of knowledge. But I have nothing to apply it toward.

What am I supposed to do with that? Well, that’s where The Church of the Black Sun comes in.

My spiritual journey has been a lifelong adventure to say the least, full of highs and lows, lots of questions, a few revelations, and more dead ends than I can count. And much has happened over the past year to lead me to at least three significant conclusions. I don’t know where they’ll lead me, but at least they provide a basic blueprint for navigating the present moment.

Let’s begin.

Church of the Black Sun Axiom No. 1: Truth is a pathless land.

His mind is not for rent

To any god or government.

— Rush, “Tom Sawyer”

Many years ago now — I no longer remember how — I came across the writings of Jiddu Krishnamurti. Plucked from obscurity as a boy in India, K (as he was often called) was groomed to become the “World Teacher,” in essence a messiah for the modern age. His mentor, Annie Besant, was the head of the Theosophical Society, a religious organization that blended esoteric Western teachings with traditional Eastern ideas. She established The Order of the Star as a vehicle to prepare K for his role as a contemporary savior.

Except that things didn’t turn out as expected, because K himself blew up the order with a speech before 3,000 onlookers on August 3, 1929. The nature of his own spiritual revelation gave him no other choice, as he came to believe that truth can’t be found through a guru such as the one he was being prepared to become. In fact, he argued, it can’t be found through any means external to oneself, because then you’re just buying into someone else’s story and not living your own truth.

Here’s how he explained it on that fateful day:

I maintain that Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. That is my point of view, and I adhere to that absolutely and unconditionally. Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or to coerce people along any particular path. If you first understand that, then you will see how impossible it is to organize a belief. A belief is purely an individual matter, and you cannot and must not organize it. If you do, it becomes dead, crystallized; it becomes a creed, a sect, a religion, to be imposed on others. This is what everyone throughout the world is attempting to do. Truth is narrowed down and made a plaything for those who are weak, for those who are only momentarily discontented. Truth cannot be brought down; rather the individual must make the effort to ascend to it. You cannot bring the mountaintop to the valley. If you would attain to the mountaintop you must pass through the valley, climb the steeps, unafraid of the dangerous precipices.

In other words, no one else can put in the hard work for you to discover truth. Once you hand over the job to someone else, you submit to that person’s creed, which means you end up handing over your mind as well. Group creeds become ideologies to be imposed on their members, and often on others outside the group. By definition, this replaces an authentic search for truth with the imposition of rigid dogma. When you look at our modern world and see the often fanatical devotion people give to their political tribes, you can see that K was absolutely correct. The same, then, applies to all religious sects, and to any group where you have to sacrifice your conscience and your freedom of thought to be accepted into the tribe.

Truth, then, can only ever be an individual pursuit, and K decided to devote the rest of his life to helping free people from the bondage of dogmatism.

I do not want followers, and I mean this. The moment you follow someone you cease to follow Truth. I am not concerned whether you pay attention to what I say or not. I want to do a certain thing in the world and I am going to do it with unwavering concentration. I am concerning myself with only one essential thing: to set man free. I desire to free him from all cages, from all fears, and not to found religions, new sects, nor to establish new theories and new philosophies.

[…] Because I am free, unconditioned, whole — not the part, not the relative, but the whole Truth that is eternal — I desire those who seek to understand me to be free; not to follow me, not to make out of me a cage which will become a religion, a sect. Rather should they be free from all fears — from the fear of religion, from the fear of salvation, from the fear of spirituality, from the fear of love, from the fear of death, from the fear of life itself.

I’m sure K was aware of the irony that he, the consummate anti-guru, spent the following decades speaking before thousands of enthusiastic people who reverently hung on his every word, only for him to tell them, over and over again, that they needed to look to themselves to find their truth — not to him, and not to anyone else.

As someone who’s never been able to fully hand over the sovereignty of his mind to any tribe, party, organization, or creed, even on occasions when I almost wanted to, I instantly found K’s words resonating with me upon discovering them. They aren’t easy words to follow, because even misfits like me want to feel a sense of belonging to something. I think we all do at some level. But that approach isn’t likely to bring us happiness.

I was aware of K’s words even as I tried to force Christianity back into my life as an adult. It was never an easy thing to do, because I have a hard time taking things on blind faith or accepting other people’s teachings without subjecting them to my own scrutiny. My first job was in journalism because I had the kind of brain that wanted to get at the facts, independently of how I felt about things or even wanted them to be. I even showed signs of that mindset as a kid, when I had an endless number of questions about what I was expected to believe — to the great exasperation of my parents, who just wanted me to sit down, listen to the priest, and trust his authority.

When no one could answer my questions about Christianity to my satisfaction, I drifted off in early adulthood into Buddhism and remained there for a good 15 years. But it eventually proved to be as much of a spiritual and philosophical dead-end for me as Christianity had been. At least Christianity was part of my cultural milieu, so I eventually decided to give it another try — first through the lens of the Quakers, who have a contemplative tradition much like the Buddhists.

|

Quakers gather quietly in a circle, in an unadorned meeting space. When the Spirit moves you, you rise, address the congregation, and sit back down, after which the meeting continues in silence until someone else rises to speak. Sometimes, no one ever speaks and the meeting passes in complete silence. I’ve been to a few of those, and the feeling of a spiritual presence is especially palpable when no one breaks the quiet. It’s hard to explain unless you’ve experienced it yourself.

But when it became clear that the Quakers had drifted from their Sermon on the Mount-centric religious views and become something more akin to a far-left political action group with a thin veneer of spirituality drizzled over the top, I moved on again. Quakers have always been politically active — in fact, they were leaders in the Abolitionist movement and helped win political protections for conscientious objectors to war — but when the people who rose to speak in many of the meetings I attended seemed apologetic even mentioning religion and sounded like they’d gotten their virtue-signaling talking points straight from the DNC, I could no longer relate.

To give you an idea, the last Quaker meeting I ever attended had a quote in the weekly bulletin from John Woolman, an 18th-century Quaker, with era-appropriate references to the deity as “he” replaced with a multiple choice “he/she/zir/they.” Bye-bye, Woke Quakers.

So I kept seeking, but I also found no satisfaction in the mainline Protestant denominations. Some were flaky left-liberals like the Quakers, some held on to wacky Calvinist theology, some were too emotional and evangelical, and some seemed to just enjoy bashing Catholics and anyone else who wasn’t a member of that particular sect.

I absolutely adored the beauty and tradition of Orthodoxy. But it’s not easy to break in to Orthodox communities, especially those that cater to specific ethnic groups. I always felt like an outsider looking in at Greek and Russian Orthodox churches, since I’m neither Greek nor Russian.

So eventually, I came back to Catholicism, almost by default. I still didn’t really believe, but I resolved to take the teachings on faith the best I could and immersed myself in the comfort and familiarity of the reverent Catholic rituals I’d grown up with. I even got my daughter on course to be baptized.

But then the COVID hysteria hit good and hard, and rather than welcome people in with open arms — just as Jesus fearlessly welcomed the sick when no others would go near them, reminding us as Scripture does over and over to “be not afraid” — our churches instead shut the people out before the lockdowns even went into effect. It was as if the bishops couldn’t wait to be rid of us. At first I sought out an Orthodox church as a replacement, but then the Orthodox churches closed too.

That whole process revealed to me, more clearly than even the Catholic priest abuse scandals had, where the church’s priorities truly lay. It told me loud and clear that those in charge of the church didn’t really believe the words they preached every day. It was all just hot air, the perpetuation of ancient myths to mollify the public and keep the institution alive.

I loved the Orthodox liturgy so much that if I ever did go back to church, I’d probably give Orthodoxy another swing. Likewise, I still admire the ethical teachings of Jesus as laid out in the Sermon on the Mount, and one reason I was attracted to the Quakers, as well as to Anabaptist sects like the Mennonites, was that they put the ethics of the Sermon on the Mount at the center of their theology — as it should be, in my view. Anyone can profess belief, but how do you demonstrate your beliefs in everyday life in your interactions with others? That’s where the rubber really meets the road. How well you live out the Sermon on the Mount is pretty much a litmus test for how well you succeed in being Christ-like in this lifetime.

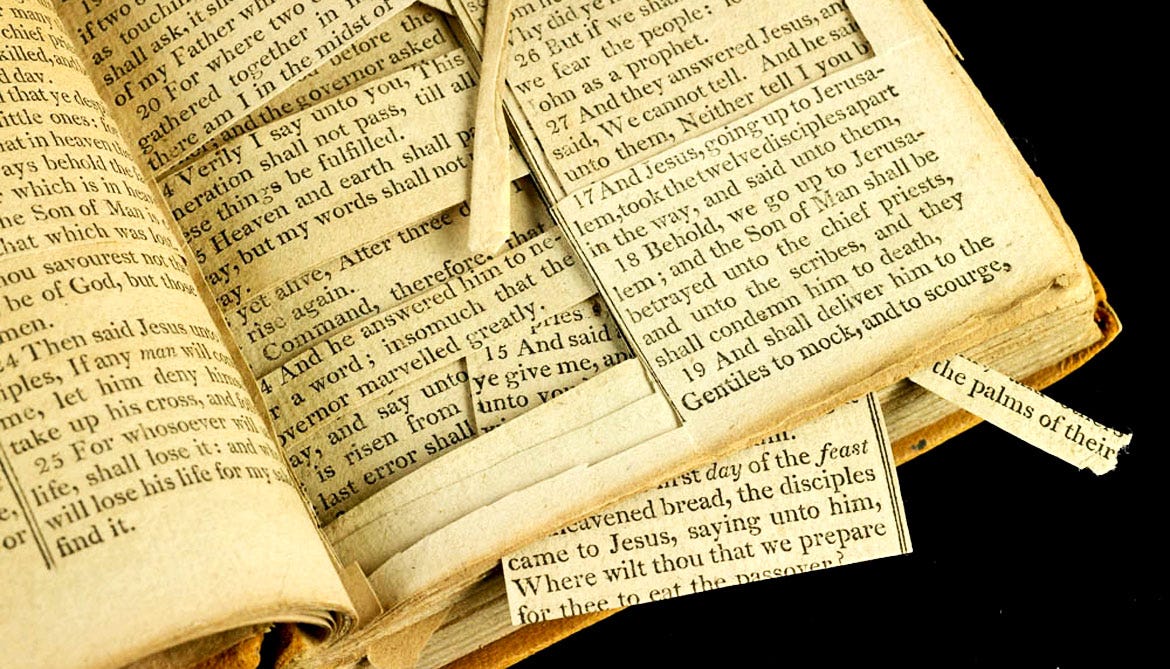

But the superstitious bullshit that makes up so much of the Bible and church theology is just that, and it deserves to be treated accordingly, especially when it’s either used to emotionally abuse people into living their lives in perpetual fear, or weaponized to judge and persecute nonbelievers. Little wonder that Thomas Jefferson cut and pasted the Gospels into a new version of the Bible that kept Jesus’ teachings intact while excising the rest that served no practical purpose.

|

| One of Jefferson’s sourcebooks for cutting up the Gospels. Image source: National Museum of American History, by way of Flickr. |

Jefferson probably would have admired Krishnamurti, for Jefferson himself once spoke of the importance of following one’s own muse, rather than give one’s mind over to someone else’s agenda:

I never submitted the whole system of my opinions to the creed of any party of men whatever, in religion, in philosophy, in politics, or in anything else, where I was capable of thinking for myself. Such an addiction is the last degradation of a free and moral agent. If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.

Or as Noam Chomsky put it plainly, in more recent times: “I was never aware of any other option but to question everything.”

In Part 2, I’ll talk more about the importance of questioning what you’re told, and why it’s OK even if your examination of the way things are leads you to a dark place.

No comments:

Post a Comment